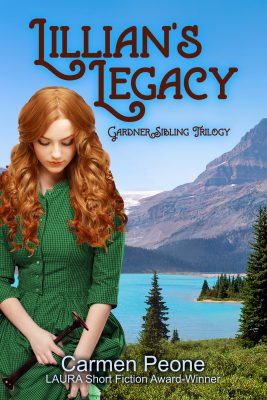

Welcome to Lillian’s Legacy Cover Reveal Party!

Welcome to the party!!

It’s cover reveal day!

What do you think?

Thanks to Rachel Rossano of Rosanno Designs for this beautiful cover of Lillian’s Legacy!

A little bit about the book:

Lillian Gardner, a healer in the making using natural medicines, is certain she is the black sheep of the family. In an attempt to prove she is of value, she sets off into the wilds of Eastern Washington and Indian Territory with Doctor Mali Maddox, an elderly Welsh female physician whose husband has recently passed away.

She hopes to marry her knowledge of herbal remedies learned from her mother and an Indian healer with new ways of western medicine. Will Lillian discover her true calling? Will she be respected as a female physician in training?

Notice what’s in Lillian’s hand?

It’s one of the first instruments used to listen to a heartbeat. If you missed it, my last blog post was about monaural stethoscopes?

I have a special guest with us to help celebrate the cover reveal.

Please welcome:

The Indigenous Art of Making Canoes with Shawn Brigman, Ph.D.

If you remember, Doctor Brigman constructed the tule-mat lodge on the cover of Heart of Passion.

Lillian’s main mode of transportation in Lillian’s Legacy is her bay gelding, Asa. When she and Doctor Maddox travel to the Pend Oreille Territory, they come across the Kalispeliwho tribe and their canoes. In one scene Lillian delivers a baby in the middle of the Pend Oreille River in a… canoe!

Enjoy my conversation with Doctor Shawn Brigman.

What led you to learn how to craft canoes?

In 2004, I studied abroad in Copenhagen, Denmark with a focus on Scandinavian architecture. During that time, I visited the Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde, Denmark to research the museum architecture housing the historical Viking ship collection archeologically recovered from the nearby fjord. At first sight of the amazing ship collection inside the museum, I knew we had a Plateau boat or canoe heritage back home and understood then that I would someday make a physical example of our Plateau canoe heritage. In 2007, I also studied abroad in Christchurch, New Zealand with a focus on Diversified Maori Tourism. During this time, I experienced many of the diversified Indigenous tourism products of the Maori, and determined that architecture, language, and culture were the three main categories connected equally in a circle that really stood out to me in reference to learning about the local Indigenous history. The Maori canoe heritage was also evident in the major museums that I visited in Aukland and Wellington. The Maori culture seemed to be tied into diverse tourism at the local, regional, and national levels on a very sophisticated level. When I returned to Washington State, naturally my inspiration and focus were on Plateau art and architecture recovery. Bark sturgeon nose canoes, tule mat lodges, fish basket traps, and pithouses, are just some of the signifying examples of Plateau built environment heritage.

Video (35 minute): Visiting Artist Museum of Glass Tacoma

How did you learn about making canoes?

In 2011 I was invited by the Northwest Museum of American Cultures in Spokane, WA to show staff members how to erect a conical tule mat lodge for their Lasting Heritage Exhibition. During this time, I scheduled a visit with the 1909 Chief Masselow bark sturgeon nose canoe in the special collections as it was the first western white pine bark canoe I examined in person hands-on. In June of 2012, I was then invited to attend a western white pine bark harvest workshop demonstration conducted by the Kalispel Tribe near Priest River, Idaho. Coincidentally, two weeks after the Kalispel bark harvest workshop, I was invited to present my tule mat lodge recovery work during the Lower Kootenai Bands sturgeon nose canoe workshop in Creston, British Columbia. Attending the Lower Kootenai Band canoe workshop, I learned how to identify the variety of canoe materials in the field as well as the processing of the material, although I was not able to stay for the actual assembly of the canoe. The next month in July of 2012, I then set out to make my first canoe frame using materials harvested from the Twin Lakes area as well as an area north of Kettle Falls, which is the ancestral homelands of the Sinixt. Thus, it is a Sinixt bark sturgeon nose canoe, even though the bark came out of Priest River, Idaho.

What was the first canoe you made?

The first bark sturgeon nose canoe frame I made was inspired by the western white pine bark harvest workshop of the Kalispel Tribe and the materiality identification and processing workshop of the Lower Kootenai Band. However, my first canoe frame sat in storage from the Fall of 2012 until May of 2018 when I finally secured canoe quality western white pine bark out of north Idaho to put on the frame.

What tools are needed for making a canoe, both bark and dugout?

To make my first ever Sinixt bark sturgeon nose canoe in 2012, I used recycled tools gifted to me by a close family friend who was a sanitation engineer (garbage collection) for the city of Spokane for 20 years. During his time in garbage collection, he collected occasional tools that were throw-away items. This included an axe, spoke shave, hook knife, and planer. Historically, Plateau ancestors had access to similar woodworking tools when fur trade stations were set up. For dugout canoes, an adze (straight and gutter), scorp, axe, and drawknife are a few of the tools used for the task.

How long have you been making them?

I have been making a variety of canoes since 2012. 2021 will be my 10th year.

What types of canoes do you normally craft? What is your favorite kind to work on and why?

All the canoes I have made are equally my favorite to work on. I have sculpted 4 traditional all-natural bark sturgeon nose canoes since 2012. In addition, I developed an original (copyrighted) canoe interpretation in 2013 with a unique frame assemblage and fabric skin attachment methodology now widely known across the Plateau region as a Salishan Sturgeon Nose Canoe (SSNC). I often give presentations or lectures on the SSNC sculptural form, with well over 30 of these canoes in circulation.

Most recently, I started exploring dugout canoe carving on a 2018 Evergreen State College Native Creative Development Grant where I produced a ½ scale dugout canoe model carved out of a western white pine log. This current spring, during the Covid-19 pandemic, many of my paid art gigs and opportunities have been canceled. Thus, I filled the time in with a full-scale cedar dugout canoe project.

Here are a couple of videos:

Dugout Canoe Video Link 2:

What do you do with the canoes once they are finished?

All of my canoes are functional art. They can display in art galleries one week, and then the next week they can be on ancestral waters being paddled.

Here is a photo of one of Doctor Brigman’s sturgeon nose canoes drifting on the Pend Oreille River in Usk, WA, featured on the cover of Pentiction Gallary Arts Newsletter.

Do you participate in the June river paddles up the Columbia with local tribes or have you participated in other canoe journeys with other tribes? Tell me about your experience with that if you have participated and what the journey meant to you.

I do participate in the annual river journeys with local Plateau tribes since 2016, although I have been paddling on ancestral Plateau waterways since 2013. Most recently, one of my Salishan Sturgeon Nose Canoes was blessed and launched at Selkirk College in Castlegar, British Columbia during the 2019 One River: Ethics Matter Conference organized and hosted by the MIR Centre for Peace. To have helped make these cultural canoe expressions possible is for me, as an Indigenous artist, extremely fulfilling.

One River, Ethics Matter Conference

Excerpt from Lillian’s Legacy

Late afternoon and after showing Yellow Owl the herbs she had in stock, the two women paddled downriver in a canoe in search of additional plants to dig and dry. Lillian marveled at the craftsmanship of the cedar-framed canoe with a western white pine bark covering. Ponderosa pines and cottonwood trees reflected in the water as the canoe glided across its surface. High mountains filled with trees rose on either side of the river, a prosperous valley anchoring them down. Geese honked as they flew overhead. Ducks and other fowl dove for fish.

For a moment all of her worries faded.

The greens, white, yellow, and brown in the water allowed Lillian’s mind to drift to a place she felt at peace with the world. She had always looked forward to being on the water with Spupaleena’s family. Loved fishing. Loved the calm feeling when in a canoe on a breezeless day.

A ways downriver, they pulled the canoe onto shore, grabbed digging sticks made of hardwood and deer antler, buckskin pouches, and baskets. Lillian stepped out of the canoe and examined a patch of wetland plants. Their soft green leaves were shaped like arrows and rose from the water. Yellow Owl joined her and with her hands told how ducks, other waterfowl, and songbirds feasted on the seeds while muskrat, beaver, and porcupine loved the tubers. She told a story of when her family stole the potatoes from muskrat nests when times were hard.

Dr. Shawn Brigman’s Bio

Dr. Shawn Brigman is an enrolled member of the Spokane Tribe of Indians and descendant of northern Plateau bands (Snʕáyckst – Sinixt, Sənpʕʷilx – San Poil, and Tk’emlúps te secwepemc – Shuswap). As a traditional artisan for 15 consecutive years, his creative practice has been one of project-based ancestral recovery efforts in Washington, Idaho, British Columbia, and Montana. Through his art, he aims to explore and transform the way Indigenous and settler people read Plateau architectural space by celebrating the physical revival of ancestral Plateau art and architectural heritage.

This involves working with Indigenous communities to connect to sources of Indigenous knowledge, often taking participant learners out to ancestral lands to gather a diverse range of natural materiality for ancestral structures like tule-mat lodges, pit houses, and bark sturgeon-nose canoes. In addition, Dr. Brigman developed an original (copyrighted) canoe interpretation in 2013 with a unique frame assemblage and fabric skin attachment methodology now widely known across the Plateau region as a Salishan Sturgeon Nose Canoe, and he often gives presentations or lectures on this sculptural form. During the 2016 Prayer Journey to Standing Rock, North Dakota, four of his Salishan Sturgeon Nose Canoes successfully delivered water protectors who “brushed the water” (the Salish language term for paddling) of the Missouri River to the Cannonball River, with gathered canoes from across the Pacific Northwest. His Salishan Sturgeon Nose Canoes have also made the annual Canoe Journey to Kettle Falls in honor of salmon recovery.

Wonderful article. A pleasure to learn about the craft and about someone so dedicated.

Looking forward to your new ( well researched) book, Carmen.

Thank you, Tyson! Shawn is an amazing artist and educator. I’m excited about Lillian’s Legacy release. It’s going to be a Facebook party with a couple of surprises!